Migraine

Migraine (UK: /ˈmiːɡreɪn/, US: /ˈmaɪ-/) is a genetically influenced complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea and light and sound sensitivity.

Other characterizing symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, cognitive dysfunction, allodynia, and dizziness. Exacerbation of headache symptoms during physical activity is another distinguishing feature. Up to one-third of migraine sufferers experience aura, a premonitory period of sensory disturbance widely accepted to be caused by cortical spreading depression at the onset of a migraine attack. Although primarily considered to be a headache disorder, migraine is highly heterogenous in its clinical presentation and is better thought of as a spectrum disease rather than a distinct clinical entity. Disease burden can range from episodic discrete attacks, consisting of as little as several lifetime attacks, to chronic disease.

| Migraine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Woman with migraine headache | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Headaches, nausea, sensitivity to light, sound, and smell |

| Usual onset | Around puberty |

| Duration | Recurrent, long term |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic |

| Risk factors | Family history, female |

| Differential diagnosis | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, venous thrombosis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, brain tumor, tension headache, sinusitis, cluster headache[unreliable medical source?] |

| Prevention | Propranolol, amitriptyline, topiramate |

| Medication | Ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen), triptans, ergotamines |

| Prevalence | ~15% |

Migraine is believed to be caused by a mixture of environmental and genetic factors that influence the excitation and inhibition of nerve cells in the brain. An older "vascular hypothesis" postulated that the aura of migraine is produced by vasoconstriction and the headache of migraine is produced by vasodilation, but the vasoconstrictive mechanism has been disproven, and the role of vasodilation in migraine pathophysiology is uncertain. The accepted hypothesis suggests that multiple primary neuronal impairments lead to a series of intracranial and extracranial changes, triggering a physiological cascade that leads to migraine symptomatology.

Initial recommended treatment for acute attacks is with over-the-counter analgesics (pain medication) such as ibuprofen and paracetamol (acetaminophen) for headache, antiemetics (anti-nausea medication) for nausea, and the avoidance of triggers. Specific medications such as triptans, ergotamines, or CGRP inhibitors may be used in those experiencing headaches that are refractory to simple pain medications. For individuals who experience four or more attacks per month, or could otherwise benefit from prevention, prophylactic medication is recommended. Commonly prescribed prophylactic medications include beta blockers like propranolol, anticonvulsants like sodium valproate, antidepressants like amitriptyline, and other off-label classes of medications. Preventive medications inhibit migraine pathophysiology through various mechanisms, such as blocking calcium and sodium channels, blocking gap junctions, and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases, among other mechanisms. Nonpharmacological preventative therapies include nutritional supplementation, dietary interventions, sleep improvement, and aerobic exercise.

Globally, approximately 15% of people are affected by migraine. In the Global Burden of Disease Study, conducted in 2010, migraines ranked as the third-most prevalent disorder in the world. It most often starts at puberty and is worst during middle age. As of 2016[update], it is one of the most common causes of disability.

Signs and symptoms

Migraine typically presents with self-limited, recurrent severe headache associated with autonomic symptoms. About 15–30% of people living with migraine experience episodes with aura, and they also frequently experience episodes without aura. The severity of the pain, duration of the headache, and frequency of attacks are variable. A migraine attack lasting longer than 72 hours is termed status migrainosus. There are four possible phases to a migraine attack, although not all the phases are necessarily experienced:

- The prodrome, which occurs hours or days before the headache

- The aura, which immediately precedes the headache

- The pain phase, also known as headache phase

- The postdrome, the effects experienced following the end of a migraine attack

Migraine is associated with major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. These psychiatric disorders are approximately 2–5 times more common in people without aura, and 3–10 times more common in people with aura.

Prodrome phase

Prodromal or premonitory symptoms occur in about 60% of those with migraines, with an onset that can range from two hours to two days before the start of pain or the aura. These symptoms may include a wide variety of phenomena, including altered mood, irritability, depression or euphoria, fatigue, craving for certain food(s), stiff muscles (especially in the neck), constipation or diarrhea, and sensitivity to smells or noise. This may occur in those with either migraine with aura or migraine without aura. Neuroimaging indicates the limbic system and hypothalamus as the origin of prodromal symptoms in migraine.

Aura phase

|  |

|  |

Aura is a transient focal neurological phenomenon that occurs before or during the headache. Aura appears gradually over a number of minutes (usually occurring over 5–60 minutes) and generally lasts less than 60 minutes. Symptoms can be visual, sensory or motoric in nature, and many people experience more than one. Visual effects occur most frequently: they occur in up to 99% of cases and in more than 50% of cases are not accompanied by sensory or motor effects. If any symptom remains after 60 minutes, the state is known as persistent aura.

Visual disturbances often consist of a scintillating scotoma (an area of partial alteration in the field of vision which flickers and may interfere with a person's ability to read or drive). These typically start near the center of vision and then spread out to the sides with zigzagging lines which have been described as looking like fortifications or walls of a castle. Usually the lines are in black and white but some people also see colored lines. Some people lose part of their field of vision known as hemianopsia while others experience blurring.

Sensory aura are the second most common type; they occur in 30–40% of people with auras. Often a feeling of pins-and-needles begins on one side in the hand and arm and spreads to the nose–mouth area on the same side. Numbness usually occurs after the tingling has passed with a loss of position sense. Other symptoms of the aura phase can include speech or language disturbances, world spinning, and less commonly motor problems. Motor symptoms indicate that this is a hemiplegic migraine, and weakness often lasts longer than one hour unlike other auras. Auditory hallucinations or delusions have also been described.

Pain phase

Classically the headache is unilateral, throbbing, and moderate to severe in intensity. It usually comes on gradually and is aggravated by physical activity during a migraine attack. However, the effects of physical activity on migraine are complex, and some researchers have concluded that, while exercise can trigger migraine attacks, regular exercise may have a prophylactic effect and decrease frequency of attacks. The feeling of pulsating pain is not in phase with the pulse. In more than 40% of cases, however, the pain may be bilateral (both sides of the head), and neck pain is commonly associated with it. Bilateral pain is particularly common in those who have migraine without aura. Less commonly pain may occur primarily in the back or top of the head. The pain usually lasts 4 to 72 hours in adults; however, in young children frequently lasts less than 1 hour. The frequency of attacks is variable, from a few in a lifetime to several a week, with the average being about one a month.

The pain is frequently accompanied by nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to sound, sensitivity to smells, fatigue, and irritability. Many thus seek a dark and quiet room. In a basilar migraine, a migraine with neurological symptoms related to the brain stem or with neurological symptoms on both sides of the body, common effects include a sense of the world spinning, light-headedness, and confusion. Nausea occurs in almost 90% of people, and vomiting occurs in about one-third. Other symptoms may include blurred vision, nasal stuffiness, diarrhea, frequent urination, pallor, or sweating. Swelling or tenderness of the scalp may occur as can neck stiffness. Associated symptoms are less common in the elderly.

Silent migraine

Sometimes, aura occurs without a subsequent headache. This is known in modern classification as a typical aura without headache, or acephalgic migraine in previous classification, or commonly as a silent migraine. However, silent migraine can still produce debilitating symptoms, with visual disturbance, vision loss in half of both eyes, alterations in color perception, and other sensory problems, like sensitivity to light, sound, and odors. It can last from 15 to 30 minutes, usually no longer than 60 minutes, and it can recur or appear as an isolated event.

Postdrome

The migraine postdrome could be defined as that constellation of symptoms occurring once the acute headache has settled. Many report a sore feeling in the area where the migraine was, and some report impaired thinking for a few days after the headache has passed. The person may feel tired or "hung over" and have head pain, cognitive difficulties, gastrointestinal symptoms, mood changes, and weakness. According to one summary, "Some people feel unusually refreshed or euphoric after an attack, whereas others note depression and malaise."[unreliable medical source?]

Cause

The underlying causes of migraines are unknown. However, they are believed to be related to a mix of environmental and genetic factors. They run in families in about two-thirds of cases and rarely occur due to a single gene defect. While migraines were once believed to be more common in those of high intelligence, this does not appear to be true. A number of psychological conditions are associated, including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.

Success of the surgical migraine treatment by decompression of extracranial sensory nerves adjacent to vessels suggests that migraineurs may have anatomical predisposition for neurovascular compression that may be caused by both intracranial and extracranial vasodilation due to migraine triggers. This, along with the existence of numerous cranial neural interconnections, may explain the multiple cranial nerve involvement and consequent diversity of migraine symptoms.

Genetics

Studies of twins indicate a 34% to 51% genetic influence of likelihood to develop migraine. This genetic relationship is stronger for migraine with aura than for migraines without aura. A number of specific variants of genes increase the risk by a small to moderate amount.

Single gene disorders that result in migraines are rare. One of these is known as familial hemiplegic migraine, a type of migraine with aura, which is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. Four genes have been shown to be involved in familial hemiplegic migraine. Three of these genes are involved in ion transport. The fourth is the axonal protein PRRT2, associated with the exocytosis complex. Another genetic disorder associated with migraine is CADASIL syndrome or cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. One meta-analysis found a protective effect from angiotensin converting enzyme polymorphisms on migraine. The TRPM8 gene, which codes for a cation channel, has been linked to migraines.

Triggers

Migraine may be induced by triggers, with some reporting it as an influence in a minority of cases and others the majority. Many things such as fatigue, certain foods, alcohol, and weather have been labeled as triggers; however, the strength and significance of these relationships are uncertain. Most people with migraines report experiencing triggers. Symptoms may start up to 24 hours after a trigger.

Physiological aspects

Common triggers quoted are stress, hunger, and fatigue (these equally contribute to tension headaches). Psychological stress has been reported as a factor by 50 to 80% of people. Migraine has also been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and abuse. Migraine episodes are more likely to occur around menstruation. Other hormonal influences, such as menarche, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, perimenopause, and menopause, also play a role. These hormonal influences seem to play a greater role in migraine without aura. Migraine episodes typically do not occur during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, or following menopause.

Dietary aspects

Between 12% and 60% of people report foods as triggers.

There are many reports that tyramine – which is naturally present in chocolate, alcoholic beverages, most cheeses, processed meats, and other foods – can trigger migraine symptoms in some individuals. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has been reported as a trigger for migraine, but a systematic review concluded that "a causal relationship between MSG and headache has not been proven... It would seem premature to conclude that the MSG present in food causes headache".

Environmental aspects

A 2009 review on potential triggers in the indoor and outdoor environment concluded that while there were insufficient studies to confirm environmental factors as causing migraine, "migraineurs worldwide consistently report similar environmental triggers".

Pathophysiology

Migraine is believed to be primarily a neurological disorder, while others believe it to be a neurovascular disorder with blood vessels playing the key role, although evidence does not support this completely. Others believe both are likely important. One theory is related to increased excitability of the cerebral cortex and abnormal control of pain neurons in the trigeminal nucleus of the brainstem.

Sensitization of trigeminal pathways is a key pathophysiological phenomenon in migraine. It is debatable whether sensitization starts in the periphery or in the brain.

Aura

Cortical spreading depression, or spreading depression according to Leão, is a burst of neuronal activity followed by a period of inactivity, which is seen in those with migraines with aura. There are a number of explanations for its occurrence, including activation of NMDA receptors leading to calcium entering the cell. After the burst of activity, the blood flow to the cerebral cortex in the area affected is decreased for two to six hours. It is believed that when depolarization travels down the underside of the brain, nerves that sense pain in the head and neck are triggered.

Pain

The exact mechanism of the head pain which occurs during a migraine episode is unknown. Some evidence supports a primary role for central nervous system structures (such as the brainstem and diencephalon), while other data support the role of peripheral activation (such as via the sensory nerves that surround blood vessels of the head and neck). The potential candidate vessels include dural arteries, pial arteries and extracranial arteries such as those of the scalp. The role of vasodilatation of the extracranial arteries, in particular, is believed to be significant.

Neuromodulators

Adenosine, a neuromodulator, may be involved. Released after the progressive cleavage of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine acts on adenosine receptors to put the body and brain in a low activity state by dilating blood vessels and slowing the heart rate, such as before and during the early stages of sleep. Adenosine levels have been found to be high during migraine attacks. Caffeine's role as an inhibitor of adenosine may explain its effect in reducing migraine. Low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), are also believed to be involved.

Calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRPs) have been found to play a role in the pathogenesis of the pain associated with migraine, as levels of it become elevated during an attack.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a migraine is based on signs and symptoms. Neuroimaging tests are not necessary to diagnose migraine, but may be used to find other causes of headaches in those whose examination and history do not confirm a migraine diagnosis. It is believed that a substantial number of people with the condition remain undiagnosed.

The diagnosis of migraine without aura, according to the International Headache Society, can be made according the "5, 4, 3, 2, 1 criteria," which is as follows:

- Five or more attacks – for migraine with aura, two attacks are sufficient for diagnosis.

- Four hours to three days in duration

- Two or more of the following:

- Unilateral (affecting one side of the head)

- Pulsating

- Moderate or severe pain intensity

- Worsened by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity

- One or more of the following:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Sensitivity to both light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia)

If someone experiences two of the following: photophobia, nausea, or inability to work or study for a day, the diagnosis is more likely. In those with four out of five of the following: pulsating headache, duration of 4–72 hours, pain on one side of the head, nausea, or symptoms that interfere with the person's life, the probability that this is a migraine attack is 92%. In those with fewer than three of these symptoms, the probability is 17%.

Classification

Migraine was first comprehensively classified in 1988.

The International Headache Society updated their classification of headaches in 2004. A third version was published in 2018. According to this classification, migraine is a primary headache disorder along with tension-type headaches and cluster headaches, among others.

Migraine is divided into six subclasses (some of which include further subdivisions):

- Migraine without aura, or "common migraine", involves migraine headaches that are not accompanied by aura.

- Migraine with aura, or "classic migraine", usually involves migraine headaches accompanied by aura. Less commonly, aura can occur without a headache, or with a nonmigraine headache. Two other varieties are familial hemiplegic migraine and sporadic hemiplegic migraine, in which a person has migraine with aura and with accompanying motor weakness. If a close relative has had the same condition, it is called "familial", otherwise it is called "sporadic". Another variety is basilar-type migraine, where a headache and aura are accompanied by difficulty speaking, world spinning, ringing in ears, or a number of other brainstem-related symptoms, but not motor weakness. This type was initially believed to be due to spasms of the basilar artery, the artery that supplies the brainstem. Now that this mechanism is not believed to be primary, the symptomatic term migraine with brainstem aura (MBA) is preferred. Retinal migraine (which is distinct from visual or optical migraine) involves migraine headaches accompanied by visual disturbances or even temporary blindness in one eye.

- Childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine include cyclical vomiting (occasional intense periods of vomiting), abdominal migraine (abdominal pain, usually accompanied by nausea), and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood (occasional attacks of vertigo).

- Complications of migraine describe migraine headaches and/or auras that are unusually long or unusually frequent, or associated with a seizure or brain lesion.

- Probable migraine describes conditions that have some characteristics of migraines, but where there is not enough evidence to diagnose it as a migraine with certainty (in the presence of concurrent medication overuse).

- Chronic migraine is a complication of migraines, and is a headache that fulfills diagnostic criteria for migraine headache and occurs for a greater time interval. Specifically, greater or equal to 15 days/month for longer than 3 months.

Abdominal migraine

The diagnosis of abdominal migraine is controversial. Some evidence indicates that recurrent episodes of abdominal pain in the absence of a headache may be a type of migraine or are at least a precursor to migraines. These episodes of pain may or may not follow a migraine-like prodrome and typically last minutes to hours. They often occur in those with either a personal or family history of typical migraine. Other syndromes that are believed to be precursors include cyclical vomiting syndrome and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood.

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions that can cause similar symptoms to a migraine headache include temporal arteritis, cluster headaches, acute glaucoma, meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Temporal arteritis typically occurs in people over 50 years old and presents with tenderness over the temple, cluster headache presents with one-sided nose stuffiness, tears and severe pain around the orbits, acute glaucoma is associated with vision problems, meningitis with fevers, and subarachnoid hemorrhage with a very fast onset. Tension headaches typically occur on both sides, are not pounding, and are less disabling.

Those with stable headaches that meet criteria for migraines should not receive neuroimaging to look for other intracranial disease. This requires that other concerning findings such as papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) are not present. People with migraines are not at an increased risk of having another cause for severe headaches.[citation needed]

Prevention

Preventive treatments of migraine include medications, nutritional supplements, lifestyle alterations, and surgery. Prevention is recommended in those who have headaches more than two days a week, cannot tolerate the medications used to treat acute attacks, or those with severe attacks that are not easily controlled. Recommended lifestyle changes include stopping tobacco use and reducing behaviors that interfere with sleep.

The goal is to reduce the frequency, painfulness, and duration of migraine episodes, and to increase the effectiveness of abortive therapy. Another reason for prevention is to avoid medication overuse headache. This is a common problem and can result in chronic daily headache.

Medication

Preventive migraine medications are considered effective if they reduce the frequency or severity of the migraine attacks by at least 50%. Due to few medications being approved specifically for the preventative treatment of migraine headaches; many medications such as beta-blockers, anticonvulsive agents such as topiramate or sodium valproate, antidepressants such as amitriptyline and calcium channel blockers such as flunarizine are used off label for the preventative treatment of migraine headaches. Guidelines are fairly consistent in rating the anticonvulsants topiramate and divalproex/sodium valproate, and the beta blockers propranolol and metoprolol as having the highest level of evidence for first-line use for migraine prophylaxis in adults. Propranolol and topiramate have the best evidence in children; however, evidence only supports short-term benefit as of 2020.

The beta blocker timolol is also effective for migraine prevention and in reducing migraine attack frequency and severity. While beta blockers are often used for first-line treatment, other antihypertensives also have a proven efficiency in migraine prevention, namely the calcium channel blocker verapamil and the angiotensin receptor blocker candesartan.

Tentative evidence also supports the use of magnesium supplementation. Increasing dietary intake may be better. Recommendations regarding effectiveness varied for the anticonvulsants gabapentin and pregabalin. Frovatriptan is effective for prevention of menstrual migraine.

The antidepressants amitriptyline and venlafaxine are probably also effective. Angiotensin inhibition by either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist may reduce attacks.

Medications in the anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide, including eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab, appear to decrease the frequency of migraines by one to two per month.

Alternative therapies

Acupuncture has a small effect in reducing migraine frequency, compared to sham acupuncture, a practice where needles are placed randomly or do not penetrate the skin. Physiotherapy, massage and relaxation, and chiropractic manipulation might be as effective as propranolol or topiramate in the prevention of migraine headaches; however, the research had some problems with methodology. Another review, however, found evidence to support spinal manipulation to be poor and insufficient to support its use.

Tentative evidence supports the use of stress reduction techniques such as cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, and relaxation techniques. Regular physical exercise may decrease the frequency. Numerous psychological approaches have been developed that are aimed at preventing or reducing the frequency of migraine in adults including educational approaches, relaxation techniques, assistance in developing coping strategies, strategies to change the way one thinks of a migraine attack, and strategies to reduce symptoms. Other strategies include: progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, behavioral training, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions. The medical evidence supporting the effectiveness of these types of psychological approaches is very limited.

Among alternative medicines, butterbur has the best evidence for its use. Unprocessed butterbur contains chemicals called pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs) which can cause liver damage, however there are versions that are PA free. In addition, butterbur may cause allergic reactions in people who are sensitive to plants such as ragweed. There is tentative evidence that coenzyme Q10 reduces migraine frequency.

Feverfew has traditionally been used as a treatment for fever, headache and migraine, women's conditions such as difficulties in labour and regulation of menstruation, relief of stomach ache, toothache and insect bites. During the last decades, it has mainly been used for headache and as a preventive treatment for migraine. The plant parts used for medicinal use are the dried leaves or the dried aerial parts. Several historical data supports feverfew's traditional medicinal uses. In addition, several clinical studies have been performed assessing the efficacy and safety of feverfew monotherapy in the prevention of migraine. The majority of the clinical trials favoured feverfew over placebo. The data also suggest that feverfew is associated with only mild and transient adverse effects. The frequency of migraine was positively affected after treatment with feverfew. Reduction of migraine severity was also reported after intake of feverfew and incidence of nausea and vomiting decreased significantly. No effect of feverfew was reported in one study.

There is tentative evidence for melatonin as an add-on therapy for prevention and treatment of migraine. The data on melatonin are mixed and certain studies have had negative results. The reasons for the mixed findings are unclear but may stem from differences in study design and dosage. Melatonin's possible mechanisms of action in migraine are not completely clear, but may include improved sleep, direct action on melatonin receptors in the brain, and anti-inflammatory properties.

Devices and surgery

Medical devices, such as biofeedback and neurostimulators, have some advantages in migraine prevention, mainly when common anti-migraine medications are contraindicated or in case of medication overuse. Biofeedback helps people be conscious of some physiological parameters so as to control them and try to relax and may be efficient for migraine treatment. Neurostimulation uses noninvasive or implantable neurostimulators similar to pacemakers for the treatment of intractable chronic migraine with encouraging results for severe cases. A transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator and a transcranial magnetic stimulator are approved in the United States for the prevention of migraines. There is also tentative evidence for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation decreases the frequency of migraines. Migraine surgery, which involves decompression of certain nerves around the head and neck, may be an option in certain people who do not improve with medications.

Management

There are three main aspects of treatment: trigger avoidance, acute symptomatic control, and medication for prevention. Medications are more effective if used earlier in an attack. The frequent use of medications may result in medication overuse headache, in which the headaches become more severe and more frequent. This may occur with triptans, ergotamines, and analgesics, especially opioid analgesics. Due to these concerns simple analgesics are recommended to be used less than three days per week at most.

For children, ibuprofen helps decrease pain and is the initially recommended treatment. Paracetamol does not appear to be effective in providing pain relief. Triptans are effective, though there is a risk of causing minor side effects like taste disturbance, nasal symptoms, dizziness, fatigue, low energy, nausea, or vomiting. Ibuprofen should be used less than half the days in a month and triptans less than a third of the days in a month to decrease the risk of medication overuse headache.

Analgesics

Recommended initial treatment for those with mild to moderate symptoms are simple analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or the combination of paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen), aspirin, and caffeine, although caffeine overuse can be a contributor to migraine chronification as well as a migraine trigger for many patients. Several NSAIDs, including diclofenac and ibuprofen, have evidence to support their use. Aspirin (900 to 1000 mg) can relieve moderate to severe migraine pain, with an effectiveness similar to sumatriptan. Ketorolac is available in intravenous and intramuscular formulations.

Paracetamol, either alone or in combination with metoclopramide, is another effective treatment with a low risk of adverse effects. Intravenous metoclopramide is also effective by itself. In pregnancy, paracetamol and metoclopramide are deemed safe as are NSAIDs until the third trimester.

Naproxen by itself may not be effective as a stand-alone medicine to stop a migraine headache as it is only weakly better than a placebo medication in clinical trials.

Antiemetics

Triptans

Triptans such as sumatriptan are medications used to stop an active migraine headache (an abortive medication). Triptans are the initially recommended treatments for those with moderate to severe pain from an acute migraine headache or those with milder symptoms who do not respond to simple analgesics. Triptans have been shown to be effective for both pain and nausea in up to 75% of people. There are different methods or routes of administration to take sumatriptan including oral (by mouth), injectable (subcutaneous), rectal, nasal spray, and oral dissolving tablets. For people with migraine symptoms such as nausea or vomiting, taking the abortive medicine by mouth or through the nose may be difficult. All route of administration have been shown to be effective at reducing migraine symptoms, however, nasal and injectable subcutaneous administration may result in more side effects. The adverse effects associated with rectal administration have not been well studied. Some people may find that they respond to one type of sumatriptan better than another.

Most side effects are mild, including flushing; however, rare cases of myocardial ischemia have occurred. They are thus not recommended for people with cardiovascular disease, who have had a stroke, or have migraines that are accompanied by neurological problems.[unreliable medical source?] In addition, triptans should be prescribed with caution for those with risk factors for vascular disease.[unreliable medical source?] While historically not recommended in those with basilar migraines there is no specific evidence of harm from their use in this population to support this caution. Triptans are not addictive, but may cause medication-overuse headaches if used more than 10 days per month.

Sumatriptan does not prevent other migraine headaches from starting in the future. For increased effectiveness at stopping migraine symptoms, a combined therapy that includes sumatriptan and naproxen may be suggested.

CGRP receptor antagonists

Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists (CGRP) target calcitonin gene-related peptide or its receptor to prevent migraine headaches or reduce their severity. CGRP is a signaling molecule as well as a potent vasodilator that is involved in the development of a migraine headache. There are four injectable monoclonal antibodies that target CGRP or its receptor (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and the medications have demonstrated efficacy in the preventative treatment of episodic and chronic migraine headaches in phase III randomized clinical trials.

Zavegepant was approved for medical use in the United States in March 2023.

Ergotamines

Ergotamine and dihydroergotamine are older medications still prescribed for migraines, the latter in nasal spray and injectable forms. They appear equally effective to the triptans and experience adverse effects that typically are benign. In the most severe cases, such as those with status migrainosus, they appear to be the most effective treatment option. They can cause vasospasm including coronary vasospasm and are contraindicated in people with coronary artery disease.

Magnesium

Magnesium is recognized as an inexpensive, over-the-counter supplement which can be part of a multimodal approach to migraine reduction. Some studies have shown to be effective in both preventing and treating migraine in intravenous form. The intravenous form reduces attacks as measured in approximately 15–45 minutes, 120 minutes, and 24-hour time periods, magnesium taken orally alleviates the frequency and intensity of migraines.

Other

Intravenous metoclopramide, intravenous prochlorperazine, or intranasal lidocaine are other potential options. Metoclopramide or prochlorperazine are the recommended treatment for those who present to the emergency department. Haloperidol may also be useful in this group. A single dose of intravenous dexamethasone, when added to standard treatment of a migraine attack, is associated with a 26% decrease in headache recurrence in the following 72 hours. Spinal manipulation for treating an ongoing migraine headache is not supported by evidence. It is recommended that opioids and barbiturates not be used due to questionable efficacy, addictive potential, and the risk of rebound headache. There is tentative evidence that propofol may be useful if other measures are not effective.

Occipital nerve stimulation, may be effective but has the downsides of being cost-expensive and has a significant amount of complications.

There is modest evidence for the effectiveness of non-invasive neuromodulatory devices, behavioral therapies and acupuncture in the treatment of migraine headaches. There is little to no evidence for the effectiveness of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation and dietary approaches to the treatment of migraine headaches. Behavioral treatment of migraine headaches may be helpful for those who may not be able to take medications (for example pregnant women).

Feverfew is registered as a traditional herbal medicine in the Nordic countries under the brand name Glitinum, only powdered feverfew is approved in the Herbal community monograph issued by European Medicines Agency (EMA).

Topiramate and botulinum toxin (Botox) have evidence in treating chronic migraine. Botulinum toxin has been found to be useful in those with chronic migraine but not those with episodic ones. The anti-CGRP monoclonal antibody erenumab was found in one study to decrease chronic migraines by 2.4 days more than placebo.

Prognosis

"Migraine exists on a continuum of different attack frequencies and associated levels of disability." For those with occasional, episodic migraine, a "proper combination of drugs for prevention and treatment of migraine attacks" can limit the disease's impact on patients' personal and professional lives. But fewer than half of people with migraine seek medical care and more than half go undiagnosed and undertreated. "Responsive prevention and treatment of migraine is incredibly important" because evidence shows "an increased sensitivity after each successive attack, eventually leading to chronic daily migraine in some individuals." Repeated migraine results in "reorganization of brain circuitry," causing "profound functional as well as structural changes in the brain." "One of the most important problems in clinical migraine is the progression from an intermittent, self-limited inconvenience to a life-changing disorder of chronic pain, sensory amplification, and autonomic and affective disruption. This progression, sometimes termed chronification in the migraine literature, is common, affecting 3% of migraineurs in a given year, such that 8% of migraineurs have chronic migraine in any given year." Brain imagery reveals that the electrophysiological changes seen during an attack become permanent in people with chronic migraine; "thus, from an electrophysiological point of view, chronic migraine indeed resembles a never-ending migraine attack." Severe migraine ranks in the highest category of disability, according to the World Health Organization, which uses objective metrics to determine disability burden for the authoritative annual Global Burden of Disease report. The report classifies severe migraine alongside severe depression, active psychosis, quadriplegia, and terminal-stage cancer.

Migraine with aura appears to be a risk factor for ischemic stroke doubling the risk. Being a young adult, being female, using hormonal birth control, and smoking further increases this risk. There also appears to be an association with cervical artery dissection. Migraine without aura does not appear to be a factor. The relationship with heart problems is inconclusive with a single study supporting an association. Migraine does not appear to increase the risk of death from stroke or heart disease. Preventative therapy of migraines in those with migraine with aura may prevent associated strokes. People with migraine, particularly women, may develop higher than average numbers of white matter brain lesions of unclear significance.

Epidemiology

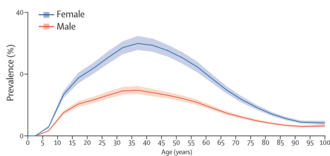

Migraine is common, with around 33% of women and 18% of men affected at some point in their lifetime. Onset can be at any age, but prevalence rises sharply around puberty, and remains high until declining after age 50. Before puberty, boys and girls are equally impacted, with around 5% of children experiencing migraines. From puberty onwards, women experience migraines at greater rates than men. From age 30 to 50, up to 4 times as many women experience migraines as men.

Worldwide, migraine affects nearly 15% or approximately one billion people. In the United States, about 6% of men and 18% of women experience a migraine attack in a given year, with a lifetime risk of about 18% and 43% respectively. In Europe, migraines affect 12–28% of people at some point in their lives with about 6–15% of adult men and 14–35% of adult women getting at least one yearly. Rates of migraine are slightly lower in Asia and Africa than in Western countries. Chronic migraine occurs in approximately 1.4 to 2.2% of the population.

In women, migraine without aura are more common than migraine with aura; however in men the two types occur with similar frequency.

During perimenopause symptoms often get worse before decreasing in severity. While symptoms resolve in about two-thirds of the elderly, in 3–10% they persist.

History

An early description consistent with migraine is contained in the Ebers Papyrus, written around 1500 BCE in ancient Egypt.

The word migraine is from the Greek ἡμικρᾱνίᾱ (hēmikrāníā), 'pain in half of the head', from ἡμι- (hēmi-), 'half' and κρᾱνίον (krāníon), 'skull'.

In 200 BCE, writings from the Hippocratic school of medicine described the visual aura that can precede the headache and a partial relief occurring through vomiting.

A second-century description by Aretaeus of Cappadocia divided headaches into three types: cephalalgia, cephalea, and heterocrania. Galen of Pergamon used the term hemicrania (half-head), from which the word migraine was eventually derived. He also proposed that the pain arose from the meninges and blood vessels of the head. Migraine was first divided into the two now used types – migraine with aura (migraine ophthalmique) and migraine without aura (migraine vulgaire) in 1887 by Louis Hyacinthe Thomas, a French Librarian. The mystical visions of Hildegard von Bingen, which she described as "reflections of the living light", are consistent with the visual aura experienced during migraines.

Trepanation, the deliberate drilling of holes into a skull, was practiced as early as 7,000 BCE. While sometimes people survived, many would have died from the procedure due to infection. It was believed to work via "letting evil spirits escape". William Harvey recommended trepanation as a treatment for migraines in the 17th century. The association between trepanation and headaches in ancient history may simply be a myth or unfounded speculation that originated several centuries later. In 1913, the world-famous American physician William Osler misinterpreted the French anthropologist and physician Paul Broca's words about a set of children's skulls from the Neolithic age that he found during the 1870s. These skulls presented no evident signs of fractures that could justify this complex surgery for mere medical reasons. Trepanation was probably born of superstitions, to remove "confined demons" inside the head, or to create healing or fortune talismans with the bone fragments removed from the skulls of the patients. However, Osler wanted to make Broca's theory more palatable to his modern audiences, and explained that trepanation procedures were used for mild conditions such as "infantile convulsions headache and various cerebral diseases believed to be caused by confined demons."

While many treatments for migraine have been attempted, it was not until 1868 that use of a substance which eventually turned out to be effective began. This substance was the fungus ergot from which ergotamine was isolated in 1918. Methysergide was developed in 1959 and the first triptan, sumatriptan, was developed in 1988. During the 20th century with better study-design, effective preventive measures were found and confirmed.

Society and culture

Migraine is a significant source of both medical costs and lost productivity. It has been estimated that migraine is the most costly neurological disorder in the European Community, costing more than €27 billion per year. In the United States, direct costs have been estimated at $17 billion, while indirect costs – such as missed or decreased ability to work – is estimated at $15 billion. Nearly a tenth of the direct cost is due to the cost of triptans. In those who do attend work during a migraine attack, effectiveness is decreased by around a third. Negative impacts also frequently occur for a person's family.

Research

Potential prevention mechanisms

Transcranial magnetic stimulation shows promise, as does transcutaneous supraorbital nerve stimulation. There is preliminary evidence that a ketogenic diet may help prevent episodic and long-term migraine.

Potential sex dependency

While no definitive proof has been found linking migraine to sex, statistical data indicates that women may be more prone to having migraine, showing migraine incidence three times higher among women than men. The Society for Women's Health Research has also mentioned hormonal influences, mainly estrogen, as having a considerable role in provoking migraine pain. Studies and research related to the sex dependencies of migraine are still ongoing, and conclusions have yet to be achieved.

See also

References

Further reading

- Ashina M (November 2020). Ropper AH (ed.). "Migraine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (19): 1866–1876. doi:10.1056/nejmra1915327. PMID 33211930. S2CID 227078662.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Billinghurst L, Potrebic S, Gersz EM, Gloss D, et al. (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 500–509. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105. PMC 6746206. PMID 31413170.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Holler-Managan Y, Potrebic S, Billinghurst L, Gloss D, et al. (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 487–499. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. PMID 31413171. S2CID 199662718.

External links

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Sex(ism), Drugs, and Migraines, Distillations Podcast, Science History Institute, 15 January 2019 Sex(ism), Drugs, and Migraines, Distillations Podcast, Science History Institute, 15 January 2019 |

This article uses material from the Wikipedia English article Migraine, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license ("CC BY-SA 3.0"); additional terms may apply (view authors). Content is available under CC BY-SA 4.0 unless otherwise noted. Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.

®Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wiki Foundation, Inc. Wiki English (DUHOCTRUNGQUOC.VN) is an independent company and has no affiliation with Wiki Foundation.