Kepler's Laws Of Planetary Motion

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, published by Johannes Kepler between 1609 and 1619, describe the orbits of planets around the Sun.

The laws modified the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus, replacing its circular orbits and epicycles with elliptical trajectories, and explaining how planetary velocities vary. The three laws state that:

- The orbit of a planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.

- A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

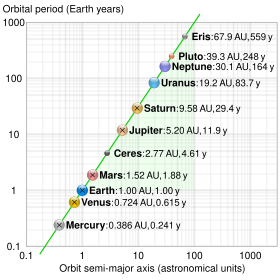

- The square of a planet's orbital period is proportional to the cube of the length of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

- The orbits are ellipses, with foci F1 and F2 for Planet 1, and F1 and F3 for Planet 2. The Sun is at F1.

- The shaded areas A1 and A2 are equal, and are swept out in equal times by Planet 1's orbit.

- The ratio of Planet 1's orbit time to Planet 2's is .

The elliptical orbits of planets were indicated by calculations of the orbit of Mars. From this, Kepler inferred that other bodies in the Solar System, including those farther away from the Sun, also have elliptical orbits. The second law helps to establish that when a planet is closer to the Sun, it travels faster. The third law expresses that the farther a planet is from the Sun, the slower its orbital speed, and vice versa.

Isaac Newton showed in 1687 that relationships like Kepler's would apply in the Solar System as a consequence of his own laws of motion and law of universal gravitation.

A more precise historical approach is found in Astronomia nova and Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae.

Comparison to Copernicus

Johannes Kepler's laws improved the model of Copernicus. According to Copernicus:

- The planetary orbit is a circle with epicycles.

- The Sun is approximately at the center of the orbit.

- The speed of the planet in the main orbit is constant.

Despite being correct in saying that the planets revolved around the Sun, Copernicus was incorrect in defining their orbits. Introducing physical explanations for movement in space beyond just geometry, Kepler correctly defined the orbit of planets as follows:: 53–54

- The planetary orbit is not a circle with epicycles, but an ellipse.

- The Sun is not at the center but at a focal point of the elliptical orbit.

- Neither the linear speed nor the angular speed of the planet in the orbit is constant, but the area speed (closely linked historically with the concept of angular momentum) is constant.

The eccentricity of the orbit of the Earth makes the time from the March equinox to the September equinox, around 186 days, unequal to the time from the September equinox to the March equinox, around 179 days. A diameter would cut the orbit into equal parts, but the plane through the Sun parallel to the equator of the Earth cuts the orbit into two parts with areas in a 186 to 179 ratio, so the eccentricity of the orbit of the Earth is approximately

which is close to the correct value (0.016710218). The accuracy of this calculation requires that the two dates chosen be along the elliptical orbit's minor axis and that the midpoints of each half be along the major axis. As the two dates chosen here are equinoxes, this will be correct when perihelion, the date the Earth is closest to the Sun, falls on a solstice. The current perihelion, near January 4, is fairly close to the solstice of December 21 or 22.

Nomenclature

It took nearly two centuries for the current formulation of Kepler's work to take on its settled form. Voltaire's Eléments de la philosophie de Newton (Elements of Newton's Philosophy) of 1738 was the first publication to use the terminology of "laws". The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers in its article on Kepler (p. 620) states that the terminology of scientific laws for these discoveries was current at least from the time of Joseph de Lalande. It was the exposition of Robert Small, in An account of the astronomical discoveries of Kepler (1814) that made up the set of three laws, by adding in the third. Small also claimed, against the history, that these were empirical laws, based on inductive reasoning.

Further, the current usage of "Kepler's Second Law" is something of a misnomer. Kepler had two versions, related in a qualitative sense: the "distance law" and the "area law". The "area law" is what became the Second Law in the set of three; but Kepler did himself not privilege it in that way.

History

Kepler published his first two laws about planetary motion in 1609, having found them by analyzing the astronomical observations of Tycho Brahe.: 53 Kepler's third law was published in 1619. Kepler had believed in the Copernican model of the Solar System, which called for circular orbits, but he could not reconcile Brahe's highly precise observations with a circular fit to Mars' orbit – Mars coincidentally having the highest eccentricity of all planets except Mercury. His first law reflected this discovery.

In 1621, Kepler noted that his third law applies to the four brightest moons of Jupiter. Godefroy Wendelin also made this observation in 1643. The second law, in the "area law" form, was contested by Nicolaus Mercator in a book from 1664, but by 1670 his Philosophical Transactions were in its favour. As the century proceeded it became more widely accepted. The reception in Germany changed noticeably between 1688, the year in which Newton's Principia was published and was taken to be basically Copernican, and 1690, by which time work of Gottfried Leibniz on Kepler had been published.

Newton was credited with understanding that the second law is not special to the inverse square law of gravitation, being a consequence just of the radial nature of that law, whereas the other laws do depend on the inverse square form of the attraction. Carl Runge and Wilhelm Lenz much later identified a symmetry principle in the phase space of planetary motion (the orthogonal group O(4) acting) which accounts for the first and third laws in the case of Newtonian gravitation, as conservation of angular momentum does via rotational symmetry for the second law.

Formulary

The mathematical model of the kinematics of a planet subject to the laws allows a large range of further calculations.

First law

The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the sun at one of the two foci.

Mathematically, an ellipse can be represented by the formula:

where

For an ellipse 0 < ε < 1 ; in the limiting case ε = 0, the orbit is a circle with the Sun at the centre (i.e. where there is zero eccentricity).

At θ = 0°, perihelion, the distance is minimum

At θ = 90° and at θ = 270° the distance is equal to

At θ = 180°, aphelion, the distance is maximum (by definition, aphelion is – invariably – perihelion plus 180°)

The semi-major axis a is the arithmetic mean between rmin and rmax:

The semi-minor axis b is the geometric mean between rmin and rmax:

The semi-latus rectum p is the harmonic mean between rmin and rmax:

The eccentricity ε is the coefficient of variation between rmin and rmax:

The area of the ellipse is

The special case of a circle is ε = 0, resulting in r = p = rmin = rmax = a = b and A = πr2.

Second law

A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

The orbital radius and angular velocity of the planet in the elliptical orbit will vary. This is shown in the animation: the planet travels faster when closer to the Sun, then slower when farther from the Sun. Kepler's second law states that the blue sector has constant area.

In a small time

The area enclosed by the elliptical orbit is

and the mean motion of the planet around the Sun

satisfies

And so,

Third law

The ratio of the square of an object's orbital period with the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit is the same for all objects orbiting the same primary. However, the law holds true only for planets with small eccentricities near zero.

This captures the relationship between the distance of planets from the Sun, and their orbital periods.

Kepler enunciated in 1619 this third law in a laborious attempt to determine what he viewed as the "music of the spheres" according to precise laws, and express it in terms of musical notation. It was therefore known as the harmonic law.

Using Newton's law of gravitation (published 1687), this relation can be found in the case of a circular orbit by setting the centripetal force equal to the gravitational force:

Then, expressing the angular velocity ω in terms of the orbital period

A more detailed derivation can be done with general elliptical orbits, instead of circles, as well as orbiting the center of mass, instead of just the large mass. This results in replacing a circular radius,

where

Table

The following table shows the data used by Kepler to empirically derive his law:

| Planet | Mean distance to sun (AU) | Period (days) |  (10-6 AU3/day2) (10-6 AU3/day2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.389 | 87.77 | 7.64 |

| Venus | 0.724 | 224.70 | 7.52 |

| Earth | 1 | 365.25 | 7.50 |

| Mars | 1.524 | 686.95 | 7.50 |

| Jupiter | 5.20 | 4332.62 | 7.49 |

| Saturn | 9.510 | 10759.2 | 7.43 |

Upon finding this pattern Kepler wrote:

I first believed I was dreaming... But it is absolutely certain and exact that the ratio which exists between the period times of any two planets is precisely the ratio of the 3/2th power of the mean distance.

— translated from Harmonies of the World by Kepler (1619)

For comparison, here are modern estimates:[citation needed]

| Planet | Semi-major axis (AU) | Period (days) |  (10-6 AU3/day2) (10-6 AU3/day2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.38710 | 87.9693 | 7.496 |

| Venus | 0.72333 | 224.7008 | 7.496 |

| Earth | 1 | 365.2564 | 7.496 |

| Mars | 1.52366 | 686.9796 | 7.495 |

| Jupiter | 5.20336 | 4332.8201 | 7.504 |

| Saturn | 9.53707 | 10775.599 | 7.498 |

| Uranus | 19.1913 | 30687.153 | 7.506 |

| Neptune | 30.0690 | 60190.03 | 7.504 |

Planetary acceleration

Isaac Newton computed in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica the acceleration of a planet moving according to Kepler's first and second laws.

- The direction of the acceleration is towards the Sun.

- The magnitude of the acceleration is inversely proportional to the square of the planet's distance from the Sun (the inverse square law).

This implies that the Sun may be the physical cause of the acceleration of planets. However, Newton states in his Principia that he considers forces from a mathematical point of view, not a physical, thereby taking an instrumentalist view. Moreover, he does not assign a cause to gravity.

Newton defined the force acting on a planet to be the product of its mass and the acceleration (see Newton's laws of motion). So:

- Every planet is attracted towards the Sun.

- The force acting on a planet is directly proportional to the mass of the planet and is inversely proportional to the square of its distance from the Sun.

The Sun plays an unsymmetrical part, which is unjustified. So he assumed, in Newton's law of universal gravitation:

- All bodies in the Solar System attract one another.

- The force between two bodies is in direct proportion to the product of their masses and in inverse proportion to the square of the distance between them.

As the planets have small masses compared to that of the Sun, the orbits conform approximately to Kepler's laws. Newton's model improves upon Kepler's model, and fits actual observations more accurately. (See two-body problem.)

Below comes the detailed calculation of the acceleration of a planet moving according to Kepler's first and second laws.

Acceleration vector

From the heliocentric point of view consider the vector to the planet

where

Differentiate the position vector twice to obtain the velocity vector and the acceleration vector:

So

Inverse square law

Kepler's second law says that

The transversal acceleration

So the acceleration of a planet obeying Kepler's second law is directed towards the Sun.

The radial acceleration

Kepler's first law states that the orbit is described by the equation:

Differentiating with respect to time

Differentiating once more

The radial acceleration

Substituting the equation of the ellipse gives

The relation

This means that the acceleration vector

is the unit vector pointing from the Sun towards the planet, and

is the unit vector pointing from the Sun towards the planet, and  is the distance between the planet and the Sun.

is the distance between the planet and the Sun. Since mean motion

The inverse square law is a differential equation. The solutions to this differential equation include the Keplerian motions, as shown, but they also include motions where the orbit is a hyperbola or parabola or a straight line. (See Kepler orbit.)

Newton's law of gravitation

By Newton's second law, the gravitational force that acts on the planet is:

where

is the gravitational constant.

is the gravitational constant. The acceleration of Solar System body number i is, according to Newton's laws:

is the mass of body j,

is the mass of body j,  is the distance between body i and body j,

is the distance between body i and body j,  is the unit vector from body i towards body j, and the vector summation is over all bodies in the Solar System, besides i itself.

is the unit vector from body i towards body j, and the vector summation is over all bodies in the Solar System, besides i itself. In the special case where there are only two bodies in the Solar System, Earth and Sun, the acceleration becomes

If the two bodies in the Solar System are Moon and Earth the acceleration of the Moon becomes

So in this approximation, the Moon moves around the Earth according to Kepler's laws.

In the three-body case the accelerations are

These accelerations are not those of Kepler orbits, and the three-body problem is complicated. But Keplerian approximation is the basis for perturbation calculations. (See Lunar theory.)

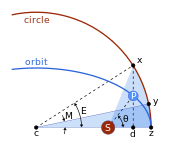

Position as a function of time

Kepler used his two first laws to compute the position of a planet as a function of time. His method involves the solution of a transcendental equation called Kepler's equation.

The procedure for calculating the heliocentric polar coordinates (r,θ) of a planet as a function of the time t since perihelion, is the following five steps:

- Compute the mean motion n = (2π rad)/P, where P is the period.

- Compute the mean anomaly M = nt, where t is the time since perihelion.

- Compute the eccentric anomaly E by solving Kepler's equation: where

is the eccentricity.

- Compute the true anomaly θ by solving the equation:

- Compute the heliocentric distance r: where

is the semimajor axis.

The position polar coordinates (r,θ) can now be written as a Cartesian vector

The important special case of circular orbit, ε = 0, gives θ = E = M. Because the uniform circular motion was considered to be normal, a deviation from this motion was considered an anomaly.

The proof of this procedure is shown below.

Mean anomaly, M

The Keplerian problem assumes an elliptical orbit and the four points:

- s the Sun (at one focus of ellipse);

- z the perihelion

- c the center of the ellipse

- p the planet

and

distance between center and perihelion, the semimajor axis,

the eccentricity,

the semiminor axis,

the distance between Sun and planet.

the direction to the planet as seen from the Sun, the true anomaly.

The problem is to compute the polar coordinates (r,θ) of the planet from the time since perihelion, t.

It is solved in steps. Kepler considered the circle with the major axis as a diameter, and

the projection of the planet to the auxiliary circle

the point on the circle such that the sector areas |zcy| and |zsx| are equal,

the mean anomaly.

The sector areas are related by

The circular sector area

The area swept since perihelion,

Eccentric anomaly, E

When the mean anomaly M is computed, the goal is to compute the true anomaly θ. The function θ = f(M) is, however, not elementary. Kepler's solution is to use

Division by a2/2 gives Kepler's equation

This equation gives M as a function of E. Determining E for a given M is the inverse problem. Iterative numerical algorithms are commonly used.

Having computed the eccentric anomaly E, the next step is to calculate the true anomaly θ.

But note: Cartesian position coordinates with reference to the center of ellipse are (a cos E, b sin E)

With reference to the Sun (with coordinates (c,0) = (ae,0) ), r = (a cos E – ae, b sin E)

True anomaly would be arctan(ry/rx), magnitude of r would be √r · r.

True anomaly, θ

Note from the figure that

Dividing by

The result is a usable relationship between the eccentric anomaly E and the true anomaly θ.

A computationally more convenient form follows by substituting into the trigonometric identity:

Get

Multiplying by 1 + ε gives the result

This is the third step in the connection between time and position in the orbit.

Distance, r

The fourth step is to compute the heliocentric distance r from the true anomaly θ by Kepler's first law:

Using the relation above between θ and E the final equation for the distance r is:

See also

- Circular motion

- Free-fall time

- Gravity

- Kepler orbit

- Kepler problem

- Kepler's equation

- Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

- Specific relative angular momentum, relatively easy derivation of Kepler's laws starting with conservation of angular momentum

Explanatory notes

Citations

General bibliography

- Kepler's life is summarized on pages 523–627 and Book Five of his magnum opus, Harmonice Mundi (harmonies of the world), is reprinted on pages 635–732 of On the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy (works by Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, and Einstein). Stephen Hawking, ed. 2002 ISBN 0-7624-1348-4

- A derivation of Kepler's third law of planetary motion is a standard topic in engineering mechanics classes. See, for example, pages 161–164 of Meriam, J.L. (1971) [1966]. Dynamics, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-59601-1..

- Murray and Dermott, Solar System Dynamics, Cambridge University Press 1999, ISBN 0-521-57597-4

- V. I. Arnold, Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Chapter 2. Springer 1989, ISBN 0-387-96890-3

External links

- B.Surendranath Reddy; animation of Kepler's laws: applet Archived 2013-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- "Derivation of Kepler's Laws" (from Newton's laws) at Physics Stack Exchange.

- Crowell, Benjamin, Light and Matter, an online book that gives a proof of the first law without the use of calculus (see section 15.7)

- David McNamara and Gianfranco Vidali, "Kepler's Second Law – Java Interactive Tutorial", an interactive Java applet that aids in the understanding of Kepler's Second Law.

- Cain, Gay (May 10, 2010), Astronomy Cast, "Ep. 189: Johannes Kepler and His Laws of Planetary Motion"

- University of Tennessee's Dept. Physics & Astronomy: Astronomy 161, "Johannes Kepler: The Laws of Planetary Motion"

- Equant compared to Kepler: interactive model [1] Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine[dead link]

- Kepler's Third Law:interactive model [2] Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine[dead link]

- Solar System Simulator (Interactive Applet) Archived 2018-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kepler and His Laws" in From Stargazers to Starships by David P. Stern (10 October 2016)

- "Kepler's Three Laws of Planetary Motion" on YouTube by Jens Puhle (Dec 27, 2023) - a video explaining and visualizing Kepler's three laws of planetary motion

This article uses material from the Wikipedia English article Kepler's laws of planetary motion, which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license ("CC BY-SA 3.0"); additional terms may apply (view authors). Content is available under CC BY-SA 4.0 unless otherwise noted. Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.

®Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wiki Foundation, Inc. Wiki English (DUHOCTRUNGQUOC.VN) is an independent company and has no affiliation with Wiki Foundation.